“קולו של הבבלי: בכבלי מסורת ותמורה” – על ספרו של מולי וידס – איתי מרינברג-מיליקובסקי

Moulie Vidas, Tradition and the Formation of the Talmud, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2014.

שני חלקי הספר מטפלים בנושאים ידועים למדי. הראשון, צורני או ‘ספרותי’ במהותו, מוקדש לבעיית היחסים בין רבדיה השונים של הסוגיה התלמודית (פרקים 1-3); השני, תמאטי ו’אידיאולוגי’ במובהק, כרוך בנטיית הבבלי אל החידוש היצירתי (פרקים 4-6). את שניהם מחברת בהצלחה (ואולי, ליתר דיוק, הצלחה יחסית) שאלת הזיקה אל המסורת: עריכת הבבלי במבנה רב-שכבתי מורכב משקפת, לדעת וידאס, עמדה מסוימת באשר לטיבן של מסורות קדומות – והיא היא שמשתקפת גם בהעדפת ‘עוקר ההרים’ על ה’סיני’. תבנית הספר מניחה רמת הלימה גבוהה בין צורה ותוכן, ולכך אשוב בהמשך; בשני המקרים, מכל מקום, מילת המפתח היא ‘אי-המשכיות’ (discontinuity): הבבלי, וּוידאס בעקבותיו, מַבנה, מסמן, מדגיש ואף חוגג את הפער בין מקור לדיון בו, בין ידע לניתוחו, בין ‘מסורת’ ל’מוסרים’; הוא עושה זאת בהצהרות גלויות, הנדונות בחלקו השני של הספר, ובדרכים שקטות יותר, הנדונות בחלקו הראשון.

לא יפלא, אפוא, כי החיבור שלפנינו מנכיח בדרכים שונות את דמות עורכיו של הבבלי, שאת קולם – ‘קולו’ של הבבלי, מכנה אותו המחבר לפעמים– אפשר לאתר בקלות, אם רק מאזינים כראוי:

If we think of the Talmud’s creators mostly as introducing unconscious modifications, as hiding themselves behind their traditions and retrojecting their own words and ideas into them, as adapting tradition to new context and ‘improve’ it, it is because we have focused on these specific activities and not others. The Bavli’s creators themselves are not hiding: they are there in almost every sugya, structuring the discussion and leading the reader (or listener) through the sources, expressing their voice in the anonymous discussion that organizes most of the Talmud. While their choice of anonymity in itself might be seen as an act of deference toward their predecessors, their literary practice betrays a different set of priorities. (p.11)

בהעמידו בסיס קונספטואלי לפרקים הפרשניים שיבואו אחריו, סוקר המבוא לספר גישות מרכזיות בשאלת היחסים בין ‘קולו’ של הבבלי עצמו לקולות המצוטטים בו. גישות אלה נכרכות בידי וידאס בתמורות שחלו בעת החדשה בהמשגת ה’מסורת’, כמו גם בהתפתחויות בחקר התרבויות האוראליות, ובהטמעת השיח על אודות פרקטיקות של ‘מְחבּרוּת’ (authorship. * מונח עברי אלגנטי יותר יתקבל בברכה) – הן כאשר תמורות אלה מוזכרות בכתבי מקצת מן החוקרים ומשמשות להם השראה גלויה, והן, מודה וידאס, כאשר הן בבחינת ‘נוכח-נפקד’ בעבודתם של חוקרים אחרים.

הפרק הראשון דן בסוגיית הפתיחה של מסכת בבא קמא, ומראה כיצד הבבלי אמנם מכשיר את הקרקע לשילוב עמדת אחד האמוראים (במקרה זה, רב פפא) במסגרת הדיון הסתמאי, אך בה בעת מבליט את חוסר ההלימה בין דבריו ובין העמדה המובלעת של הדיון המקדים. כך למשל מזהה וידאס בקריאתו הרגישה מתח בין עיצוב עמדת הסוגיה בגוף ראשון רבים, לעיצוב עמדת האמורא נקוב-השם בגוף שני יחיד; מתח הנתפס על ידו כביטוי סימפטומטי להתמודדות עם מסורת העבר, המוצגת ברגיל כ’אחרת’ (ולפיכך כתלויית-הקשר), בניגוד להווה ‘שלנו’ (קרי, של עורכי הסוגיה), הנהנה מזכות-היתר של קביעת ההקשר, ובכך מפקיע את עצמו מקונטקסטואליזציה מצמצמת.

בפרק השני מנווט המחבר את דרכו בזהירות במחלוקת על אודות היחסים הכרונולוגיים בין החומר הסתמאי והחומר נקוב-השם, מחלוקת שהדיה ניכרים כמעט בכל דיון משמעותי בבבלי בעשורים האחרונים. וידאס מציע לראות את ההפרדה בין חומרים משני הסוגים – כלומר, את ריבוד (layerization) הטקסט התלמודי – כקונסטרוקט ספרותי של עורכי התלמוד ויוצריו; חומרים ארץ-ישראליים (במקרה הנדון בפרק זה, ובמקרים רבים אחרים) מאורגנים מחדש בסוגיה הבבלית בשכבות האופייניות לה, תוך הפרדת המסורת מהאנליזה, או כפי שהדברים מנוסחים לקראת סוף הפרק – תוך הפרדה בין שכבה מצוּטטת לשכבה מצטטת. הפער בין השכבות, לגבי דידו, אינו משקף פער היסטורי בהתהוותן, אלא מעשה עריכה מתוחכם המתמודד באמצעים סגנוניים עם הקונפליקט בין מסירה וחידוש:

The layered structure… combined a commitment to a faithful transmission of tradition and an independent and flexible engagement with that tradition. It allowed Babylonian scholar to contrast their own approaches with the teachings of the past, whether to showcase the scholarly virtuosity of an individual scholar or more generally to mark the distance between a classical past and their own age. The adoption of this structure was a move toward a more marked distinction between tradition and innovation. (p. 78)

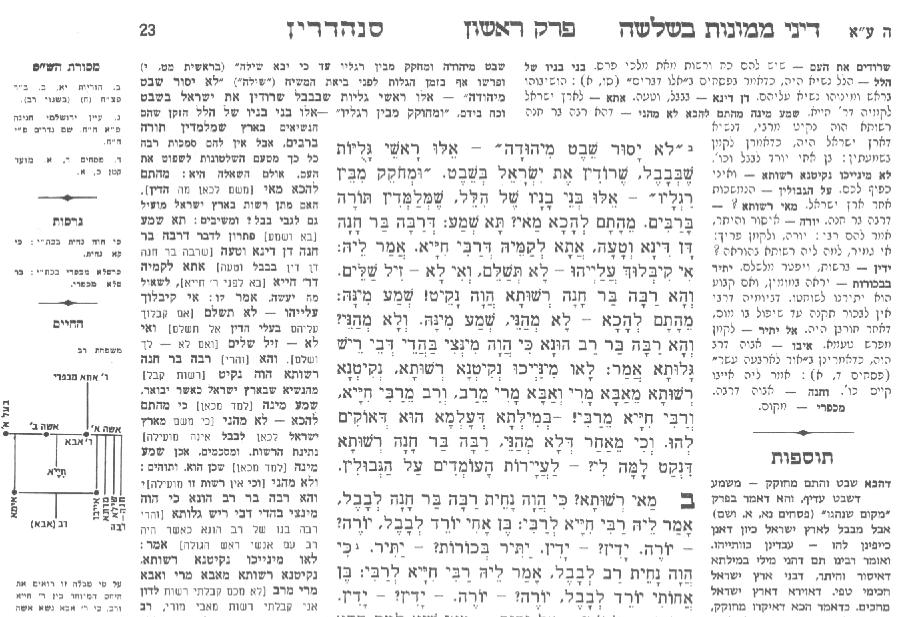

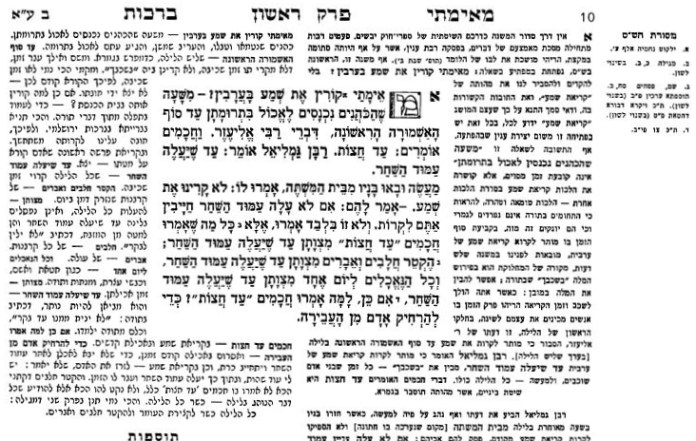

במקום אחר בפרק מדגיש המחבר כי התלמוד עצמו – רוצה לומר, הטקסט הערוך, הסופי, ‘קולו של הבבלי’ שכבר הוזכר לעיל – הוא שמייחד מונחי ציטוט להבאת מימרות וברייתות, ומותיר את השכבה הסתמאית בלעדיה; התלמוד עצמו הוא שמעצב לעתים, אם גם לא תמיד, הבדלי שפה (עברית-ארמית) בין החלקים נקובי-השם לחלקים הסתמאיים. טיעונים אלה מודגמים בניתוח סוגיה ממסכת פסחים: וידאס מיטיב לשכנע כי במקרה זה הבבלי והירושלמי חולקים לא רק תשתית למדנית משותפת, אלא אף אבחנה פנימית בין אלמנטים נקובי-שם לאלמנטים סתמאיים, אלא שהבבלי מארגן אותם מחדש. ברוח זו, ובניגוד לרושם העולה לעתים ממחקרים המוקדשים לתופעות אלה, מטעים המחבר כי הבבלי אינו מוסיף מסגרת ספרותית לחומרים שחסרו אותה, כי אם מחליף מסגרת ספרותית אחת – באחרת. המסגרת החדשה מבוססת על אבחנה ההולכת ומתחדדת בין מסגרת סתמאית סיפורית-עיונית, המתווה את מהלך הסוגיה, לבין החומרים הנדונים על ידה, ויהא מקורם אשר יהא.הפרק השלישי דן בסדרה של סוגיות משלהי מסכת קידושין, ומראה כיצד אותו מרחק ביקורתי שנרקם בידי עורכי התלמוד בריבוד הסוגיות לשכבה מצוטטת ושכבה מצטטת, מושג לעיתים קרובות גם באמצעים אחרים, שאינם קשורים דווקא לפעולת הריבוד במובנה הצר. עדכון ועיבוד של מסורות ספציפיות, שינויים בפונקציות של אלמנטים בודדים במארג הסוגיה, ארגון מחודש של מבנים סיפוריים, פיתוח קומפוזיציות רטוריות מורכבות – כל אלה תורמים לא רק ל’התאמה’ של חומר ישן לסדר-יום חדש, אלא גם לעיצוב מבט ביקורתי על החומרים המיוצגים בסוגיה כ’ישנים’, או באופן רחב יותר כמורשת מן העבר.

הפרק הרביעי פותח את חלקו השני של הספר, ומציע בחינה מחודשת לתמה בבלית ידועה: אהדת החידוש כפרקטיקה למדנית ראשונה במעלה, המאפילה, בלשון המעטה, על פרקטיקות אחרות, כגון שימור והעברה של מסורות. תמה זו, שנדונה רבות במחקר, זוכה כאן לפנים חדשות, כמעט כפשוטו של ביטוי: אין היא עוד בבחינת עמדה ‘אקדמית’ תיאורטית של בעלי התלמוד ועורכיו, כי אם כלי לעיצובה של זהות עצמאית ייחודית, נבדלת מזהותם של ה’תנאים’, שתורתם מתמקדת במסירה בלבד. וידאס רואה בה עדות טקסטואלית למתח תרבותי בין קבוצות דתיות שונות בחברה היהודית בבבל, קבוצות המצטיירות על ידו במלוא ממשותן (ככל שהמקורות הספרותיים מאפשרים להעריך איזו ‘ממשות’). בהתייחסו למציאות הריאלית הוא משער, וראיותיו עִמו, שהגבול בין ‘מסרנים’ לחכמים לא היה בהכרח ברור כל כך; ממילא, תודעת הזרוּת המגדירה את היחסים ביניהם בפסקאות רבות מן הבבלי ראויה לדעתו להתפרש אף היא כקונסטרוקט ספרותי שתפקידו לגלם את המתח בין שתי הקבוצות, ובמישור סימבולי מופשט יותר – בין מסירה ואנליזה. כך מתווה הייצוג הספרותי (להבדיל מן ה’מציאות’) גבולות מובהקים בין ‘אנחנו’ (בעלי התלמוד, אנשי האנליזה), ל’הם’, כלומר, למי שמסומנים מעתה כ’אחרים’ (בעלי המשנה, ה’תנאים’ המשננים).

בהמשך לכך, הפרק החמישי עוסק בויכוח על הציטוט (או השינון), וממקם את דיוניו של הבבלי בעניין זה בתוך ההקשר הרחב יותר של העולם הסאסאני. מעתה, השוואת התנא המצטט למגוש הזורואסטרי – “דאמרי אינשי: רטין מגושא ולא ידע מאי אמר, תני תנא ולא ידע מאי אמר” (בבלי סוטה כב ע”א) – אינה מתקיימת בחלל הריק; סימוּן המצטט כ’זר’, תוך הפיכת ‘בעל התלמוד’ כנגדו לנציג אותנטי-יותר (כביכול) של התרבות היהודית, מזכירה לדעת המחבר נסיונות דומים להבניה עצמית של הקול ההגמוני הדובר בטקסטים נוצריים וזורואסטריים, דמיון הניכר מבעד להבדלים בפונקציה שממלא הזכרן-המצטט בכל אחת מתרבויות אלה.

האם לסיפור זה יש צד שני? כיצד עשויה להצטייר מערכת היחסים בין המסרנים ללמדנים, מזווית המבט של הראשונים? בהיעדר עדויות מפורשות, בגוף ראשון, לפרספקטיבה של המסרנים על אודות יחסיהם עם החכמים ‘בעלי התלמוד’, חלקו השני של הספר נחתם בנסיון מאלף לאתר קצה-חוט ל’סיפור המתנגד’ (counternarrative) שלהם. דמותם של ה’אחרים’ של הבבלי, התנאים ‘מבלי העולם’ (סוטה, שם), מגיעה אפוא לשיא ממשותה בפרק השישי, בו נבחנת ספרות ההיכלות, ובעיקר מסורת ‘שר התורה’ המשולבת בה, כצוהר אפשרי לעולמם הדתי. תוך הצבעה זהירה (ושמא זהירה מדי) על נקודות השקה אפשריות בין מסורת ‘שר התורה’ ודמותם של המסרנים המתוארים בתלמוד, משרטט וידאס קווים לדמותה של קבוצה דתית המעמידה אלטרנטיבה לתרבותם של חכמי בבל. אלטרנטיבה זו מצטיינת, בין היתר, בתפיסת מעשה הזכרון והציטוט כמעשה ליטורגי יותר מאשר אינטלקטואלי; הבנה, לגבי דידה, אינה בהכרח התכלית המרכזית של העיסוק הטקסטואלי, ואפשר אף שהיא סותרת תכליות נעלות ממנה. בתקופת הגאונים, רומז המחבר בפרק המסקנות שבסוף החיבור, משהו מן הלהט היצירתי של בעלי התלמוד הולך וקופא, בשעה שהתלות בתנאים-המסרנים הולכת וגוברת; בבל, כפי שהכרנוה, משתנה מן היסוד.

הקריאה בספר מעוררת מחשבה עד מאוד; הטקסט מתוּמרר כהלכה – כבבלי עצמו – וכל אחד מחלקיו זוכה לדברי הקדמה וסיכום מועילים, התורמים יחד להעמדת משנה סדורה ומגובשת (ואולי מוטב: ‘תלמוד סדור ומגובש’?…). את הדיון בו אבקש למקם בשלושה הקשרים שונים, הנתונים בחפיפה חלקית זה עם זה: המתודולוגי, הפואטי-רטורי, והאידיאלוגי.

ראשון – ההקשר המתודולוגי. נסיונו של המחבר לטפל בשאלות ה’גדולות’ הנוגעות לאופיו היסודי של הבבלי, ושל התרבות המשתקפת ממנו, מעלה בחריפות את בעיית מגבלותיה של הקריאה הצמודה (close reading). וידאס הוא ‘קורא צמוד’ מעולה – דוגמה טובה לכוחו הפרשני מצויה בניתוחו היפה לסוגיה מפרק ‘חלק’ בסנהדין (עמ’ 132-136) – אולם הקורא עשוי לתהות באיזו מידה הסוגיות המעטות-יחסית הנדונות בספר באופן מעמיק, יכולות להעיד על הבבלי כולו. הפתרון, לעניות דעתי, אינו טמון בוויתור על התמודדות עם אותן שאלות – מה גם שלוידאס תשובות מפרות עד מאוד – אלא בפיתוח מתודולוגיה הולמת לדיון בקורפוס רחב. ברוח זו, מעניין לחשוב על תרומתה האפשרית של ‘קריאה רחוקה’ (distant reading) מבית מדרשו של פרנקו מורטי, הן להתבוננות רפלקסיבית בכבלי הקריאה הצמודה/הקרובה, הן לבחינה שיטתית של התופעות הנבחנות בספר שלפנינו (בעיקר בחלקו הראשון). דוגמא פשוטה לכך יכולה לשמש אבחנתו של וידאס, שנזכרה לעיל, בין ייצוג דברי חכם נקוב-שם בגוף שני יחיד, לייצוג ‘קולו של הבבלי’ בגוף ראשון רבים: מדובר באבחנה לשונית-סגנונית מוגדרת הניתנת למדידה, לכימוּת ולמיפוי (באמצעים ‘אנושיים’ או ‘חישוביים’), בעזרתם ניתן יהיה להציע, בשלב ראשון, תשובות חלקיות לשאלות כגון: בכמה סוגיות היא מופיעה, ומכמה היא נעדרת? מתי הסוגיה נותנת לחכמים לדבר ‘יותר’, ומתי היא נוטלת את זכות הדיבור לעצמה? האם התופעה נפוצה יותר בסוגיות פתיחה של מסכתות ופרקים? האם יש מִתאם (קורלציה) בין הופעתה בסוגיות מסוימות, לנוכחותם של מונחי משא-ומתן קבועים-פחות-או-יותר באותן סוגיות? באיזו מידה היא משקפת הרחבה של תופעות דומות בספרות הארץ-ישראלית? ומשעה שתשובות לשאלות אלה יונחו בפנינו, יגיע זמנו של המבט הרפלקטיבי, כיאה ל’קריאה רחוקה’ טובה: מה משמעותה של התופעה? מדוע היא מתנהגת כך ולא אחרת? כיצד היא מאירה את דמותו של הקול האומר ‘אנחנו’ במרקם הטקסט התלמודי, במסגרת ה’מחזה’ הלמדני שסוגיות רבות מעמידות בפנינו? בקצרה, סקירתה לאורך ולרוחב הבבלי – הבבלי כולו – עשויה להוליד טיפולוגיה עשירה של סוגיות, מתוחה על פני ספקטרום לשוני-סגנוני נרחב, ונושאת מימד תרבותי-אידיאולוגי.

שני – ההקשר הפואטי-רטורי. וידאס מייחס לסוגיה התלמודית, בצדק, איכויות פואטיות ורטוריות מובהקות (אף על פי שמונחים אלה כמעט נעדרים מן השדה הסמנטי הרגיל בספרו). איכויות אלה, על פי רוב, מבטאות לדעתו את ‘קולו של הבבלי’ – המצטייר בין השיטין כקולו של עורך רב-עוצמה, העושה בחומריו כבתוך שלו. הנחות אלה גוררות אחריהן מערך טיעונים שלם: כך, וידאס מבכר באופן שיטתי הסברים המייחסים כוונה ומודעות ליוצרי הטקסטים (ראו לדוגמא עמ’ 143, וכמותו רבים), ומצמצם למינימום הסברים ‘טכניים’ או ‘פורמליסטיים’; כך, נקודות של מתח או של אי-התאמה מתפרשות על ידו תדיר כביטוי לכוונה חתרנית של העורכים (כפי שעולה למשל מסוף הפרק הראשון), ולא, למשל, כתוצאה מקרית של התרחבות השיח הלמדני, או של כוחות צורניים אחרים הפועלים על הסוגיה (דוגמא טובה לכך היא טיפולו במסורת על שם האל בבבלי קידושין עא ע”א, הנדונה בעמ’ 99-100). כל אלה הכרעות מטא-פרשניות סבירות, מוצדקות לגמרי במסגרת הפרדיגמה העיונית של וידאס, ואפשר גם שקשה להעניק לסוגיה משמעות בלעדיהן; אך לכל הפחות יש מקום להרהר במערכת היחסים ההדוקה הנרקמת באמצעותם, כמו גם באמצעות מבנה הספר כולו, בין צורה לתוכן – צמד הראוי בעיני למבט חשדני יותר, מסוייג במידה.

שלישי ואחרון – ההקשר האידיאולוגי. בהשראת הגותם של ולטר בנימין וג’ורג’יו אגמבן, טוען וידאס כי חשיפת מנגנונים המכוננים ‘אי-המשכיות’ בין מסורת למוסריה, מעניקה לעבר קיום עצמאי, ובמשתמע – מייחסת לו משקל רב יותר מזה שניתן לו בדגמים המדמים המשכיות הרמונית יותר בין עבר להווה. על רקע טענה זו, מעניין ואף מפתיע להשוות את תפקידם של בנימין ואגמבן בספרו של וידאס, עם התפקיד ההפוך השמור להם, להבנתי, במחקר העכשווי של הספרות העברית החדשה: בשדה זה הם מוזכרים לאחרונה שוב ושוב דווקא כמי שמאפשרים לחשוב על זיקותיה הרצופות של הספרות החדשה, החילונית-לכאורה, למקורות יניקתה הקדם-מודרניים הדתיים. הנה כי כן, בחקר הספרות הרבנית, תפיסה רציפה של המסורת – תפיסה מתבקשת למדי, כשלעצמה – מוצגת (בספר שלפנינו, ולא רק בו) כ’לא-ביקורתית-מספיק’, ולפיכך מומרת בנראטיב של שבר או סדק היסטורי-תרבותי; ובחקר הספרות החדשה, לעומת זאת, דווקא תודעת משבר היסטורי-תרבותי – תודעה מתבקשת למדי, כשלעצמה – היא שמוצגת כ’לא-ביקורתית-מספיק’, ולפיכך הולכת ומומרת בנראטיב מסורתי, הרמוני לפרקים. אני מקווה שדי באנלוגיה זו כדי לשלול – בשני השדות המחקריים – התנגדות לנראטיב אחד כאילו הוא ‘מדומיין’, והערצה לאחר כאילו הוא ‘ממשי’; נדרש כיוונוּן-תדרים עדין יותר.

אך נשוב אל העיקר: חוויית הקריאה בספרו של מולי וידאס מזכירה לעתים התבוננות בצידו הפנימי של בגד יפה. לא משום שהוא מגלה את התפרים הנסתרים המחברים את חלקיו השונים של הבגד יחד – הללו, הרי, גלויים וידועים זה מכבר לכל הרגיל בבגדים (ובהתאמה: לכל מי שרגיל בקריאה ביקורתית של הטקסט התלמודי) – אלא משום שתפרים אלה עצמם זוכים רק כך לבּוֹלטוּת אסתטית (ובהתאמה: אידיאולוגית); הם אינם רק אמצעי טכני המחבר יחד, בעדינות אלגנטית או ברישוּל גס, מרכיבים שונים, אלא מנגנון אמנותי המסמן ומבליט ומעצים את שונותם של המרכיבים המצויים משני עבריו. ומן המשל אל הנמשל: חידושיו המרשימים של וידאס אינם חושפים אלמנטים לא ידועים בטקסט התלמודי, אינם מצביעים על רובד נוסף שנותר עד כה בצֵל, אלא, בפשטות, מזמינים את הקורא לשנות את הפרספקטיבה; וזו החדשה, לטעמי, ראויה ומבטיחה ביותר.

איתי מרינברג-מיליקובסקי משלים בימים אלה את עבודת הדוקטור שלו במחלקה לספרות עברית, אוניברסיטת בן-גוריון בנגב, תחת הכותרת “למעלה מן העניין: יחסי הגומלין בין סיפור והקשרו בתלמוד הבבלי – סיפורים מרובי-הופעות כמקרה מבחן” (בהנחיית ד”ר חיים וייס ופרופ’ תמר אלכסנדר).